THE ELEPHANT MAN

(2011)

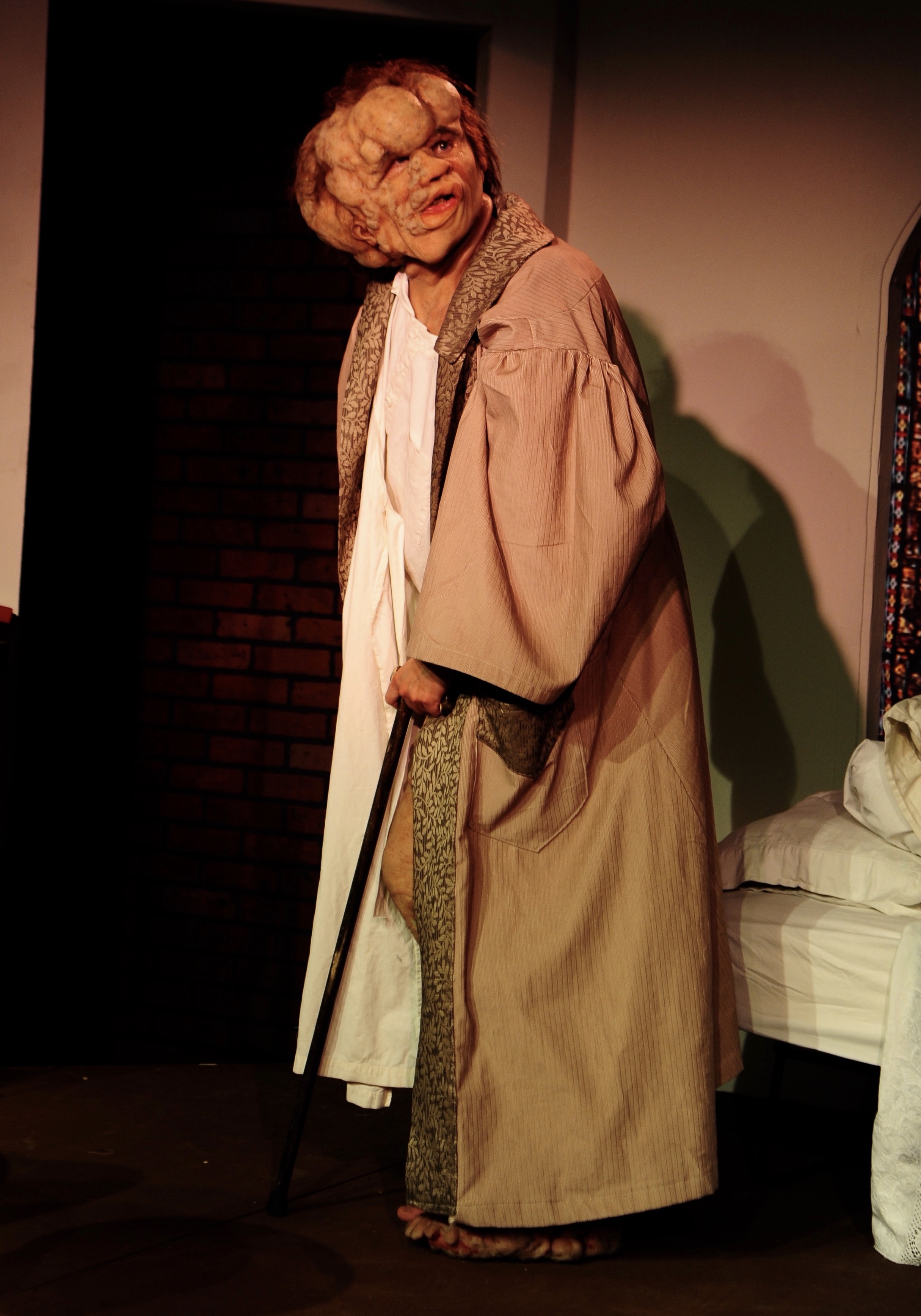

"... Sean Hoagland ... has undergone a breathtaking transformation ..."

"... a nice turn by Drouillard ..."

"... a tribute to the genius and artistry of ... makeup designer, Barney Burman."

"Hoagland is impressive as Merrick ..."

"... Hilary Herbert does a wonderful turn as Mrs. Kendal ..."

- LA Weekly

"... ambitious visual reinvention of Bernard Pomerance's 1977 masterpiece ..."

"... captivating in its ingenuity and incredibly successful in its application ..."

"... Oscar-winning special effects make-up designer Barney Burman has painstakingly re-created the actual appearance of Merrick ... quite jarring to behold ..."

"To achieve reality with Burman's stunning make-up is an amazing feat ..."

"... delicately nuanced work ..."

- Backstage

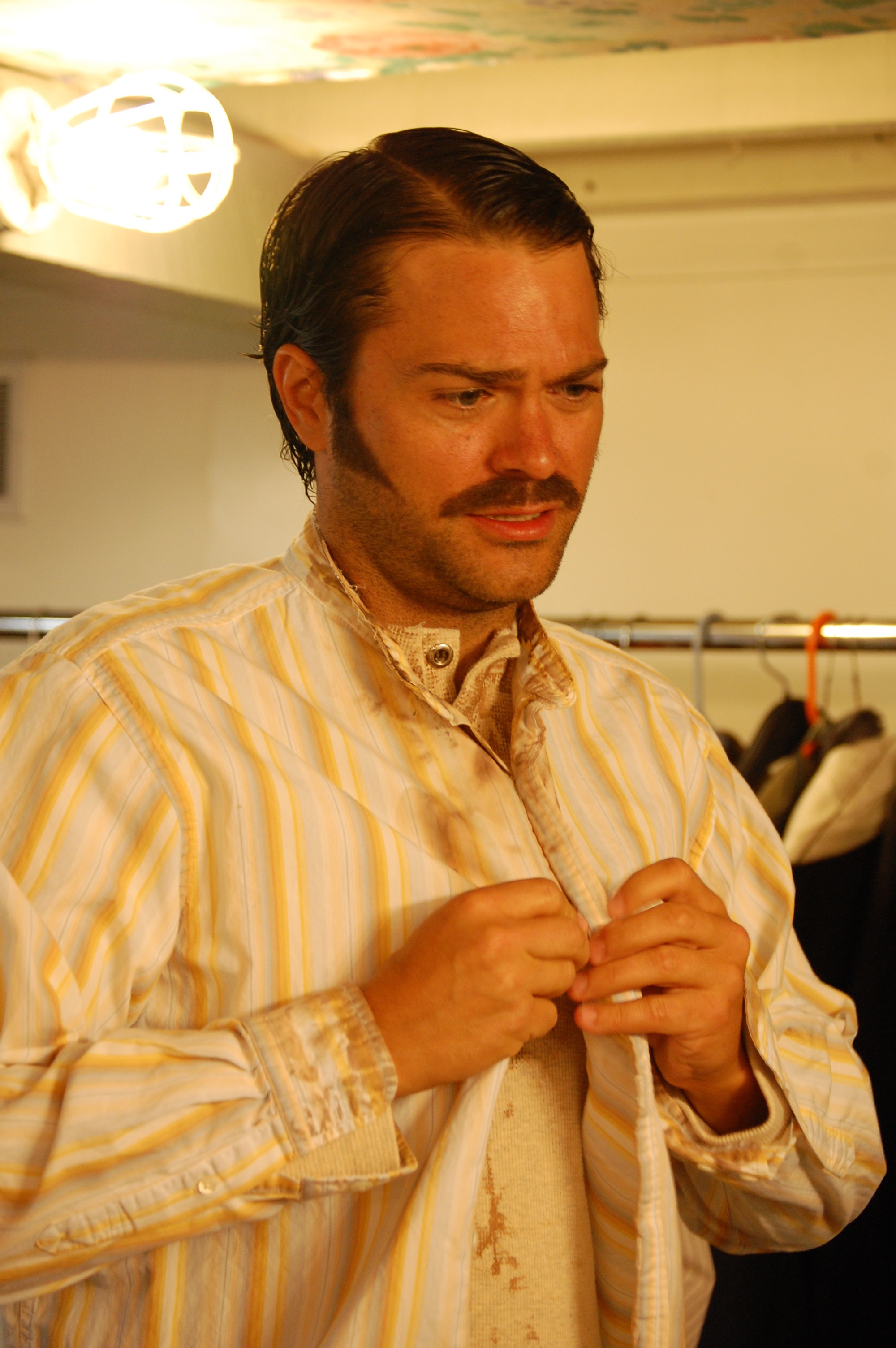

"... a bright spot in the production ... is Alex Monti Fox as Treves."

"... I'd like to see Fox try a production of EQUUS, as his approach to Treves had certain elements of Dysart ... which seemed worth exploring further."

- Talkin'Broadway

This production of THE ELEPHANT MAN by bernard pomerance was presented by Lascaux Entertainment at the El Centro Theatre Circle Stage, Hollywood, March 26-April 24, 2011, produced under special arrangement with samuel french inc.

It was directed by John Drouillard; special character design by Barney Burman and Afton Adams; costumes by Pheobe Boynton; hair and make-up design by Boutheyna Boots, Afton Adams, and Lee Komet; set design by Vali Tirsoaga; lighting by Richard Taylor; sound by Sarah Margulewicz; properties by Tamara Becker; dialect consulting by Tracy Winters; produced by John Drouillard and Natalie Drouillard; production stage manager was Sara Gunderson.

The cast was as follows:

john merrick • sean hoagland

dr. frederick treves • alex monti fox

francis carr gomm • sal viscuso

mrs. madge kendal • hilary herbert

ross • david folsom

will, lord john, liverpool policeman • bill durham

bishop walsham how, belgian policeman • trent hopkins

pinheads manager, COUNTESS • stephanie roche

miss sandwich, princess alexandra • devri richmonD

snork, conductor • caleb neet

pinhead m • margarita maliagros

pinhead l • lyndsey hogan

the giant • nick cimiluca

ABOUT THE ELEPHANT MAN

The Elephant Man is based on the life of Joseph Merrick (called “John” in Pomerance’s play,) who lived in London during the latter part of the 19th Century. Tragically disfigured from birth, Merrick was forced to support himself as a freak attraction in traveling side shows until, after being found abandoned and helpless by a prestigious young physician, Dr. Frederick Treves, he is admitted for observation at the London Hospital. Under the care of Treves, who educates the already intelligent Merrick further and introduces him to London society, Merrick is able to transcend much of his past and becomes a favorite of the aristocracy and other English celebrities. However, despite this social transformation, Merrick remains trapped in the body he was given, a grave limitation which may forever hold him at arm’s length from his dream of living the life of a normal man.

THE PRODUCTION

BEHIND THE SCENES

AFTERTHOUGHTS

When I made the decision to produce and direct the first production of The Elephant Man in which the title character would be depicted as he actually physically appeared, bucking the entire trend of the play’s decades-long history, I naturally assumed it would be a highly polarizing event. In fact, my biggest surprise was how this decision was nearly universally accepted with our audiences, including those who not only were familiar with the original production, but a number who were friends with members of the original and subsequent Broadway casts.

I’d known of the legend of the Elephant Man since I was a kid, finding out a bit of his story from books, but, pre-internet, details were hard to readily come by. I knew he was a good-hearted young man who had been in freak shows until he was befriended by a doctor at the London Hospital where he lived the rest of his life. That’s it. I knew nothing of the deeper story.

So, I was naturally interested in Bernard Pomerance’s play when it became a smash on Broadway in 1979, even more curious about the fact that Merrick was being presented with no disfiguring make-up or costuming, but only by the physical portrayal of the actor.

I wasn’t able to see the original production until a year or so later when most of the original cast was brought together for a television broadcast of it and I absolutely loved it. It was such a thrill to see the original leads perform this material, particularly Philip Anglim’s magnificent, touching portrayal of Merrick.

However, as well as it all worked, I still found myself confused at the convention of how the character was being physically portrayed, because, though the convention worked for its intended purpose, that is to remove the “distraction” of Merrick’s physical appearance so that we might know him on the inside, it didn’t really resolve for me why this was necessary, a question made even more potent after seeing David Lynch’s film version of the Elephant Man story shortly thereafter where Merrick was presented as he historically appeared, something which didn’t take anything away from how those of us in the audience felt about him.

Maybe it’s a matter of perspective. I grew up watching my father, a mountain of a strong, earnest blue collar working man, hide his hands in his pockets whenever he was in mixed company because they had been badly disfigured in a horrible fire accident when he was 19. It always made me sad to see his strength diminished simply by the leering eyes of others. And then, throughout my childhood, I knew numerous others who were chastised for their appearance and it never interfered with anybody’s ability to know these people if they only gave themselves a chance to do so.

And, by the time we produced our show, some 30 years after the original, the entire culture had evolved around the acceptance of differences, as well as acclimating ourselves to a steady diet of some of the greatest horrors we’ve ever seen, from ghastly war images from around the world to the absolute destruction and even consumption of the human body on TV during prime time. So, at this point in history and in my own particular journey, I felt it would be dishonest for me to present Merrick in any other way than he actually was. If indeed the previous decades of the show had been performed without make-up as a vehicle to allow audiences to know Merrick more deeply, I guess mine was intended as a challenge for audiences to do the same.

Much is always made, when the play is produced, about how the title actor is able to create Merrick in our minds “without the need for prosthetics to get the point across,” but little, if anything, is ever said about why we, as an audience, need to be protected or forgiven Merrick’s actual appearance in order for us to be able to know him. It certainly wasn’t a problem for those who gave Merrick a chance in the late 19th Century when they could see, hear, and smell every aspect of his condition. Indeed, they found him so wonderful that we’re still talking about him today — and not as a monster, but as a man.

I don’t know if this show will ever be performed this way again, but I’m profoundly happy we chose to do it. With all due respect to Bernard Pomerance and how this material has always been performed, I wanted to give at least one company and one set of audiences an opportunity to experience this tremendous work through the lens of a greater understanding of who the Elephant Man actually was, as well as through the lens of our own evolution as a society as we face far greater demands on our hearts and sensibilities than making the leap to know someone despite their physical differences from us.